When I launched this newsletter, a mentor of mine pointed me towards a book that ‘every filmmaker has tapped’: Man and His Symbols, by Carl Jung.

Here’s the crux of Jung’s ideas in two sentences:

Your psyche is a self-regulating organism: it compensates for conscious attitudes with unconscious expressions.

Through dreams, your unconscious urges you to follow your true nature, to achieve self-realization.

Jung believed that dreams, images generated in the sleeping brain’s visual cortex, constitute ‘a dialogue between the ego and the self’. Here the ‘ego’ refers only to the conscious mind of an individual, while the ‘self’ represents the totality of their psyche.

Sigmund Freud had already shown that consciousness, the ‘smaller circle’ within the ‘larger circle' of the unconscious, is overrated. Our thoughts, feelings, dreams and intuitions originate in the unconscious, and return there upon slipping the mind.

When you experience a flash of inspiration or an original breakthrough, it’s not a memory of something previously known. It’s an entirely new idea formed by the unconscious. But for the idea to be realized, it must first be recognized by the conscious ego. These two aspects of the mind work in concert.

Enter dreams: arriving by night, while consciousness sleeps, their function is to bring self-knowledge and balance to the ego by compensating for its deficiencies. So for example, if you’re an unconfident, diffident person who always follows others and fades into the background, you are likely to have dreams of power and leadership. Those dreams are telling you to take a more active and decisive role in life.

What does this have to do with film and myth?

Myths follow in the footsteps of dreams, and films recreate both.

First, dreams are in essence the prototypes of cinema. Both are visionary images which cut through time in a non-linear fashion, and both are symbolic, consisting of images with multiple layers of meaning: the literal and conscious alongside the metaphorical and unconscious. Many films, of course, begin as dreams.

The fact that dreams consist of pictures is paramount. Jung: these images contain personal symbols, relevant only to an individual, and collective symbols: 'archetypes'.

Defined as instinctive tendencies to form representations of a certain motif, archetypes manifest in dreams in order to reconcile opposites within one’s psyche.

Notable archetypes include the animal as an evocation of man's primitive nature, the circle as a symbol of psychic wholeness, and the stone as an inanimate vessel for the unconscious. The precise meaning of these archetypes remains fluid, easily modified to suit the needs of each individual's psyche.

Second, dreams tend to follow a meandering pattern, directed by a hidden centre: the self. This process, a coming-to-terms with our inner being, can be accelerated by conscious will; Jung called it ‘individuation’. Film writers would call it a character arc: a journey by which the protagonist overcomes their flaw and discovers their true self.

Third, dreams aim to awaken a 'recollection of the prehistoric', ie the primal instincts of humanity which are articulated by mythology. Across the planet, we give narrative expression to this through the prominence of three psychological themes.

1. The hero myth: the hero, representing the conscious ego, draws from their shadow, the dark, opposite side of their personality, to defeat their antagonist - eg a 'dragon'.

2. The initiation rite: the novice surrenders their ego and personal ambition by submitting to an 'ordeal', ie his greater sense of self, thus becoming stronger.

3. Transcendence: a release from confining patterns of existence, transcendence unifies the conscious and unconscious - eg ‘animal transformation’, ‘pilgrimage’ etc.

These motifs are different variations of the same key: the individual unites opposing forces, achieving equilibrium between their conscious and unconscious aspects.

Films, therefore, recreate dream patterns both in style and content, through their sequence and selection of images. Myths were the first stories to do this, and as humanity’s original stories, they continue to inspire filmmakers.

And well they should. As Jung saw it, modern civilization has divided consciousness from the deeper, more instinctive levels of the human psyche. Separating from nature, we have lost contact with our primal drives and instincts. Worshipping rationality, we have devalued our dreams and forgotten our symbols - yet we remain in the grip of powers beyond our control. Our gods and demons have not disappeared, they merely have new names: addiction, alienation, restlessness... neuroses beyond number.

The problem is accentuated by the fact that propaganda, advertisements, and social pressures all seduce us into following ways which are unsuitable to our individuality, and the result distances us from ourselves - it throws us out of balance.

The point is to be able to distinguish between alien distractions and your true inner voice. This isn't the place to explain how, but if you listen closely...

…

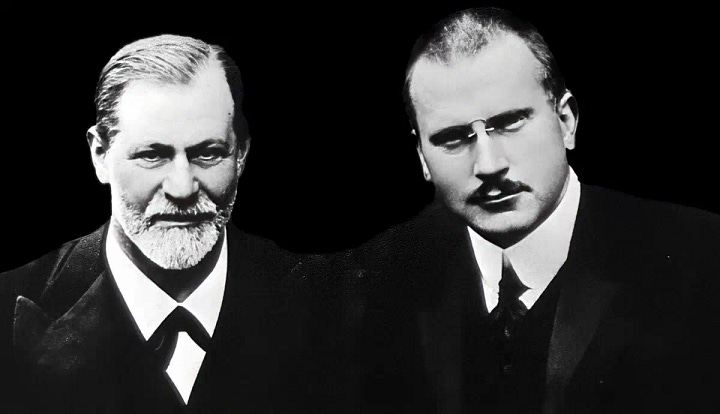

Bonus Content: The Difference Between Sigmund Freud & Carl Jung

Both men believed that dreams are the 'royal road' (Freud's words) to the unconscious. Freud saw dreams as wish-fulfilment, the articulation of desires which are repressed in waking life. In The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), he argued that the visual, 'manifest content' of a dream is a diguise for its true, 'latent content'.

The reason for this disguise is censorship. The ego (unique to the individual) and the super-ego (stemming from society) prevent the wishes of the unconscious from entering consciousness. Instead these desires emerge distorted, as dreams - a kind of partial satisfaction which enables the individual to sleep and function more generally.

Freud treated these psychological complications through a process he called 'free association': disregarding connections between the manifest content of the dream, he would encourage the dreamer to unpack each separate element in great detail. So you would 'zigzag' from the starting point of the dream until you reached its true meaning.

Jung disagreed, finding that free association led to irrelevant digressions from the actual dream. His approach was more a 'circumambulation' around a dream's centre. He asked, 'Why should dreams mean something different from their contents? Is there anything in nature that is other than what it is?' The meaning of a dream was thus to be found in its symbols, by focusing specifically on the images it conjured.

While Freud insisted that dreams expressed stifled unconscious desires, usually sexual, Jung - his former student - decided that they were symbolic unconscious messages, attempts by the self to compensate for imbalances within consciousness.

So the two men parted ways. There’s a good film about their split, starring Michael Fassbender and Viggo Mortensen: A Dangerous Method, by David Cronenberg (2011).

This combination of concepts might be the way to approach your story during the rewriting process in the future, it really caught my attention and has so much to draw from. I shared it with a friend who is working on a film about the intersection of dreams and AI with the medical field. Great work Xan! Un abrazo

“Separating from nature, we have lost contact with our primal drives and instincts. Worshipping rationality, we have devalued our dreams and forgotten our symbols - yet we remain in the grip of powers beyond our control. Our gods and demons have not disappeared, they merely have new names: addiction, alienation, restlessness... neuroses beyond number.”

—Shew. This resonated deeply with me. There will always be powers beyond our control, truths lying just outside the reach of rationality and logic. Myth and dreams can be reliable tools for grappling with those uncertainties.

Thanks for this post!